Asia

India-China Army Face-off In Galwan Valley: The Other Side of Skirmish

Recent Indo-China army brawl between both the nuclear-capable countries had raised the eyebrows of the rest of the world including superpowers amidst COVID-19 pandemic virulent attack. The gruesome battle without weapons but in most of them in scuffles, the Chinese have used bats, clubs, sticks, and stones to cause major injuries.

Nail studded rods used by the Chinese army to attack Indian soldiers

Besides the use of these blunt objects, some soldiers are said to have been pushed into the fast-flowing Galwan river. This soon led to punch-ups and blows being exchanged, resulting in deaths and injuries. More than 70 Indian soldiers were injured in a major scuffle. At least 20 soldiers including a Commanding Officer of India lost their lives on a single day.

The Chinese media did not disclose any causality from their side but from respected and reputed sources confirmed the numbers of deaths of people liberation army were more than 40.

News censorship in China

This is the first time after the 1962 war that soldiers have died in clashes on the India-China border in Ladakh. The tussle on Monday night, fought in one of the most forbidding landscapes on the planet, was a staggering accumulation of months of mounting tension and years of dispute. And it comes at a fraught moment, with the world focused on battling the coronavirus and with the nationalist leaders of both nations eager to flex their muscles.

Indo China Standoff

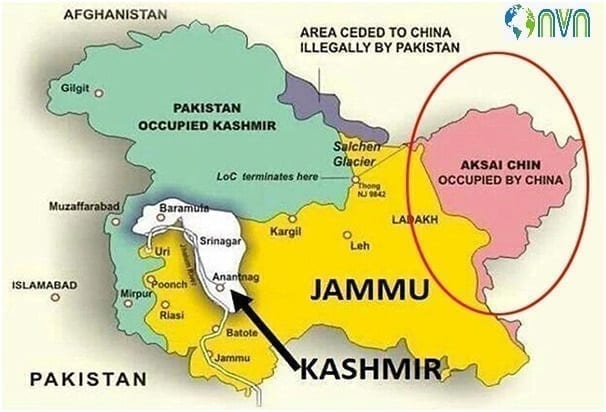

Here’s a look at how both nations arrived at this juncture, the battles that came before traced to way back 1914. The LAC is the demarcation that separates Indian-controlled territory from Chinese-controlled territory. For India, the LAC is 3,488 km long, while China considers it to be only around 2,000 km. It is divided into three sectors: the eastern sector which includes Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim, the middle sector in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh, and the western sector in Ladakh.

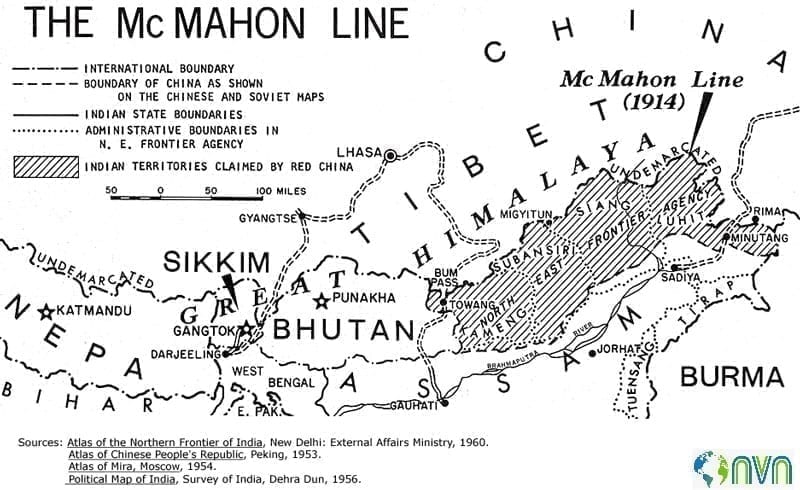

LAC in the eastern sector consisting of Arunachal Pradesh and Sikkim is called the McMahon Line which is 1,140 km long. Western Sector or Aksai Chin Sector is claimed by the Chinese government post-1962 war as an autonomous part of Xinjiang region which is originally supposed to be the part of the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir.

China’s intrusion into Indian territory

Central Sector is the less disputed section of the Indo-China border but recent Doklam standoff and Nathu La Pass trading issues have brought distress at all levels. Eastern Sector or Arunachal Pradesh has been claiming the Tawang valley and nearby area as their own.

The conflict stretches back to at least 1914, when representatives from Britain, the Republic of China, and Tibet gathered in Simla, in what is now India, to negotiate a treaty that would determine the status of Tibet and effectively settle the borders between China and British India.

McMahon Line: named after a British colonial official, Henry McMahon

The Chinese, balking at proposed conditions that would have allowed Tibet to be autonomous and remain under Chinese control, refused to sign the deal. But Britain and Tibet signed a treaty establishing what would be called the McMahon Line, named after a British colonial official, Henry McMahon, who proposed the border. India maintains that the McMahon Line, a 550-mile frontier that extends through the Himalayas, is the official legal border between China and India. But China has never accepted it.

Post Independence In 1949, the Chinese revolutionary Mao Zedong proclaimed an end to his country’s Communist Revolution and founded the People’s Republic of China.

Almost immediately, the two nuclear nations now the world’s most densely inhabited found themselves at odds over the border. Tensions rose throughout the 1950s. The Chinese insisted that Tibet was never independent and could not have signed a treaty creating an international border. There were several failed attempts at peaceful negotiation. China sought to control critical roadways near its western frontier in Xinjiang, while India and its Western allies saw any attempts at Chinese incursion as part of a wider plot to export Maoist-style Communism across the region. By 1962, the war had broken out.

1962 Indo-China War Zone

Chinese troops crossed the McMahon Line and took up positions deep in Indian territory, capturing mountain passes and towns. The war lasted one month but resulted in more than 1,000 Indian deaths and over 3,000 Indians taken as prisoners. The Chinese military suffered fewer than 800 deaths. By November, Premier Zhou Enlai of China declared a cease-fire, unofficially redrawing the border near where Chinese troops had conquered territory. It was the so-called Line of Actual Control.

Tensions came to a head again in 1967 along with two mountain passes, Nathu La and Cho La, that connected Sikkim — then a kingdom and a protectorate of India — and China’s Tibet Autonomous Region. A scuffle broke out when Indian troops began laying barbed wire along what they recognized as the border. The scuffles soon escalated when a Chinese military unit began firing artillery shells at the Indians. In the ensuing conflict, more than 150 Indians and 340 Chinese were killed. The clashes in September and October 1967 in those passes would later be considered the second all-out war between China and India.

Indo-China scuffle in 1967

But India prevailed, destroying Chinese fortifications in Nathu La and pushing them farther back into their territory near Cho La. The change in positions, however, meant that China and India each had different and conflicting ideas about the location of the Line of Actual Control.

It would be 20 more years before India and China clashed again at the disputed border. In 1987, the Indian military was conducting a training operation to see how fast it could move troops to the border. A large number of troops and material arriving next to Chinese outposts surprised Chinese commanders — who responded by advancing toward what they considered the Line of Actual Control. Realizing the potential to inadvertently start a war, both India and China de-escalated, and a crisis was averted.

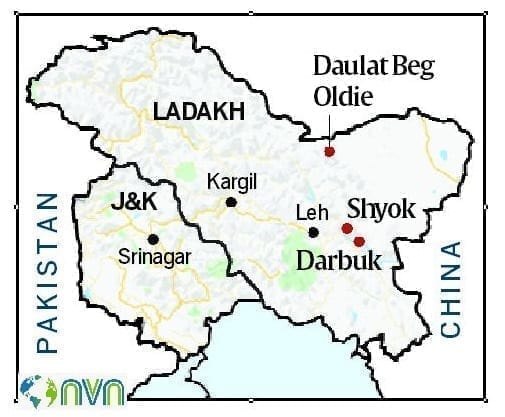

After a slew of cat-and-mouse tactics unfolded on both sides and decades of patrolling the border, a Chinese platoon pitched a camp near Daulat Beg Oldi in April 2013. The Indians soon followed, setting up their own base fewer than 1,000 feet away. The camps were later fortified by troops and heavy equipment. By May, the sides had agreed to dismantle both encampments, but disputes about the location of the Line of Actual Control persisted.

Troops near Daulat Beg Oldi

In recent times in June 2017, the Chinese set to work building a road in the Doklam Plateau, an area of the Himalayas controlled not by India, but by its ally Bhutan. The plateau lies on the border of Bhutan and China, but India sees it as a buffer zone that is close to other disputed areas with China.

Indian troops carrying weapons and operating bulldozers confronted the Chinese with the intention of destroying the road. A standoff ensued, soldiers threw rocks at each other, and troops from both sides suffered injuries. In August, the countries agreed to withdraw from the area, and China stopped construction on the road.

Our Intrusive neighbors

Finally, the question arises is whether the recent Galwan valley skirmish is the repercussion of border disputes or otherwise? The answer is a little bit sub-critical. The Galwan Valley area comes under Sub Sector North (SSN), which lies just to the east of the Siachen glacier and is the only point that provides direct access to Aksai Chin from India.

The current tensions can be traced to Chinese objections over India’s road construction activities here. China is believed to be particularly concerned about a bridge that India is building across the Galwan nallah. The bridge is part of a network of feeder roads that India is building connecting the strategically important Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldi road, inaugurated by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh last year.

Bridge built between Durbuk and Daulat Beg Oldie

Defense sources have told even though the bridge is about 7.5 km from the LAC, the Chinese have objected because they are suspicious of India’s aims on account of New Delhi’s claim over Aksai Chin. Analysts say China is suspicious that the Indian constructions in the area are meant to facilitate quick movement of soldiers if any attempt is made to recapture Aksai Chin.

The sub-critical point of discussion is the Border-Road Organisation’s ambitious road plan across the LAC. The Border Roads Organisation (BRO) is aiming to complete work on the strategic Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road by the end of this year, despite frequent Chinese objections over its construction.

Sources said that workers have started coming to Ladakh and that they are hoping to complete the entire project by the end of this year. The BRO is the in-charge of the 255 km-long strategic DSDBO.

The use of the strategic road by the Indian security forces from Leh has helped in reducing the travel time between Leh and DBO to six hours. The bridge connecting the Patrolling Point 14 in Galwan area with the territory across the Shyok River is also linked to the strategic road.

The bridge connecting the Patrolling Point 14 across the Shyok River

India and China are engaged in a standoff at multiple points along the Line of Actual Control in Eastern Ladakh where the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has amassed over 10,000 troops with its heavy artillery and armored regiments on its side of the LAC. India has also now matched the deployment by China and after the talks between the two sides at the multiple levels; they have even disengaged and retrieved from their positions by a couple of kilometers.

Amid the ongoing dispute with China in eastern Ladakh over the Chinese military buildup, the Border Roads Organisation (BRO) is looking to complete the work on the 255 Km-long strategic Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DSDBO) road including eight bridges and its blacktopping at some of the stretches by the end of this year. The use of the strategic road by the Indian security forces from Leh has helped in reducing the travel time between Leh and DBO to six hours. Earlier, the travel time between the two locations was significantly higher. The road has been in the making for over two decades now and a special focus was laid on it after the Narendra Modi government came to power in 2014.

Northern Army Commanders, the Border Roads Organisation project chief engineers and commanders of the 81 Brigade looking after DBO have been working in close coordination in the last many years to ensure that the project was completed in time and the manner in which it remains an all-weather road. The bridge connecting the Patrolling Point 14 in Galwan area with the territory across the Shyok River is also linked to the strategic road. India’s improving infrastructure could be one of the reasons behind China’s aggressive posture along the Line of Actual Control in Ladakh.

In April 2019, an 11-member motorcycle expedition completed its run from Karu near Leh to the Karakoram Pass and back, a journey of around 1,000 kilometers, over the Chang La pass, and then along the Shyok river, traversing the challenging terrain of north-eastern Ladakh at over 17,000 feet.

Motorcycle expedition Team 2019

This expedition was different from those which take place in Ladakh every summer — it was the first-ever to pass through the newly-built 255-kilometer Darbuk-Shayok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DS-DBO) road. It was from the Indian Army’s ‘Army Service Corps’, one of the primary users of this road. Critical for connectivity in north-eastern Ladakh — termed Sub-Sector North by the Army, the DS-DBO road provides all-weather access to far-flung areas abutting the 38,000 square km territory of Aksai Chin under Chinese occupation, such as the Depsang Plains, which saw a tense India-China stand-off in 2013.

Running almost parallel to the LAC, the DSDBO road, meandering through elevations ranging between 13,000 ft and 16,000 ft, took India’s Border Roads Organisation (BRO) almost two decades to construct. Its strategic importance is that it connects Leh to DBO, virtually at the base of the Karakoram Pass that separates China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region from Ladakh. DBO is the northernmost corner of Indian territory in Ladakh, in the area better known in Army parlance as Sub-Sector North.

Karakoram Highway

DBO has the world’s highest airstrip, originally built during the 1962 war but abandoned until 2008, when the Indian Air Force (IAF) revived it as one of its many Advanced Landing Grounds (ALGs) along the LAC, with the landing of an Antonov An-32. In August 2013, the IAF created history by landing one of its newly acquired Lockheed Martin C-130J-30 transport aircraft at the DBO ALG, doing away thereafter with the need to send helicopters to drop supplies to Army formations deployed along the disputed frontier.

At last, whether an amicable and plausible solution is at their disposal? But the two countries are still talking at military and diplomatic levels. So, any escalation into a major conflict looks some distance away at this moment. But conflict situations have a dynamic of their own, and events can overtake the best-laid plans.

Indo-China Military Diplomacy

A military conflict, if it occurs, can be localized to one area, can be along the whole border, or can be in any one sector. But unless there are another provocation and crisis, the two sides should be able to resolve the situation peacefully. Meanwhile, the government will place the armed forces on full alert. Simultaneously, it will continue to use diplomatic channels to resolve the crisis. Alongside, controlling the domestic messaging will be done to avoid arousing public emotions. In all, the execution of such strategies will determine the course of future action on China.